Criteria for Deploying Your Tax Dollars Effectively:

How More Accountability Can Ensure We Do the Most Good for the People Most in Need

I believe our city government can and should be more transparent and thorough when allocating and tracking your tax dollars to ensure we do the most good for those most in need.

I have devoted more than half of my 30-year career to public service through government because I want to help people in need and enable cities to thrive. As we know, a key “business model” of government is to impose taxes and fees and then to redeploy those dollars to do good for the public. Local governments are typically more equitable and fair than the private market, we can impose and enforce laws (including taxes), and our relatively large size can enable cost-saving “economies of scale.” In addition to delivering city government basics like safety, zoning, and transportation, big cities with big needs like Seattle often supplement the social services of other levels of government (county, state, federal) by providing our own subsidies, programs, and projects to help low-income and marginalized communities.

Because governments collect and spend your tax dollars — and we want to do good with those dollars — it should follow that we want to be accountable by carefully deploying the dollars in ways likely to produce positive outcomes. We certainly don’t want to misuse or squander your dollars because that would undermine both the validity and effectiveness of government. This is why it’s always surprising to me whenever governments or their officials do not employ basic due diligence procedures when deciding how to deploy your money. It’s almost as if, some public officials are afraid to ask basic questions for fear of seeming callous or uninformed when, in fact, we need answers to basic questions to make sure we are doing the most good and can continue to do so.

For example, Antonio M. Oftelie, executive director of Leadership for a Networked World at Harvard University who served on the Commission on the Future of Policing, wrote an Op Ed in Crosscut about why we must measure results for any new community safety programs. He wrote, “To be transparent and accountable, they will need systems to track incidents, analyze data and report outcomes to the public. So, while we reinvent policing, we must also rebuild human services.” For the full Op Ed, CLICK HERE.

As someone who has worked for the federal government, other local governments, and the private sector in the financial arena, I’d like to share with you the checklists I strive to consider when deciding whether a project or organization should receive your tax dollars. Frankly, legislators rely a lot on the executive branch (with their 12,000 employees vs. our 100 or so legislative staff) to make sure dollars are deployed with accountability. But legislators typically have final approval authority over the budget and we are expected to provide oversight to make sure your tax dollars are doing the good work we intended.

If we simply deploy your dollars to city government executive departments responsible for delivering proven programs and benefits for residents and communities, then that’s a good start for accountability because those employees work for the government. If, however, we are contracting out those dollars to private organizations (including nonprofits), then extra effort is warranted to keep track of your tax dollars and put in place performance-based contracts to keep track of goals and outcomes.

Unfortunately, some public officials allow tax dollars to be deployed without sufficient due diligence upfront or without specifying and measuring positive outcomes. Many politicians are adept at devising ways to spend money — spreading it around to respond to vocal and well-meaning advocacy groups — but they might not be as focused on a methodical, transparent process for deciding who receives the funds or a methodical, transparent process for tracking results. Much of the City’s $6.5 billion budget is already targeted toward those most in need and, during each annual budget season, policymakers strive to do more. Following that desire to direct more dollars should also be the desire to make sure ALL the dollars are actually achieving their goals – to ensure we are truly helping people. I will continue to demand that your tax dollars are invested effectively.

I have useful experience in awarding grants to organizations while at HUD during the Clinton Administration (homelessness and economic development), in Oakland (youth programs), and in Seattle (the evidence-based Nurse Family Partnership, Seattle Preschool Program, and the original gun safety study). As I learned the hard way, not all organizations with well-intentioned, heartfelt missions actually achieve sufficiently positive results.

Having worked in this position as a Councilmember for only one year, I’m still assessing whether the existing Seattle ordinances and procedures provide sufficient accountability when deploying your tax dollars. As with most things in a dynamic organization, I suspect there is room for improvement and will work on this accountability issue in 2021. For example, the Seattle Municipal Code (SMC) Chapter 20.50 “Procurement of Consultant Services” may need tightening by closing “loopholes” to ensure greater accountability. In a process critiqued by the independent SCC Insight, four City Councilmembers used an existing Seattle Municipal Code provision to award $3 million directly to organizations, when many (including me) had believed those funds — which we all supported for community-informed participatory budgeting — would instead be awarded through an open Request for Proposals process. (See below for several public benefits of using the best practice of an open RFP process.) In addition, when awarding funds to specific organizations, the City Council may want to beef up our analysis by adding to our Summary/Fiscal Note a clear and consistent due diligence checklist (which could include some of the financial and programmatic criteria discussed in this blog post).

As a partial defunding of our Seattle Police Department (SPD) and other budgeting efforts make available additional dollars available for alternative crime prevention and community wellness programs, we have a tremendous opportunity to put in place smart performance measures ahead of time, so we can make sure we actually deliver the positive results we all say we want. We can also fund technical assistance to empower many promising community-led organizations so they can apply for funds, track results, measure their effectiveness, and implement continuous improvements. Performance measures also enable us as policymakers to collect and review the information needed to scale up the most successful prevention and intervention anti-carceral programs proven to work so that we help more people.

Either way, basic accountability is needed to allocate dollars strategically and to ensure positive outcomes. I divide this assessment into two sections:

- Deciding who receives your money and

- Assessing effectiveness (for both social programs and capital projects):

1. DECIDING WHO RECEIVES YOUR MONEY:

The Process (transparency):

- Was a public and competitive process used to award the funds?

- A Request for Proposal (RFP) process has the benefit of having organizations think through how they would best use these tax dollars which, if successful, will give the general public more confidence to make more investments. An RFP can incorporate the other points raised here. It can also ask for things such as the budget of the organization and the proposed budget of the program(s)/project(s). This basic info helps to confirm the organization is solvent and our City dollars would not be backfilling or solving organization problems, but rather providing additive direct services to benefit city residents in need.

- An RFP would need to be affirmatively marketed so that BIPOC-led and culturally competent organizations are aware of the opportunity and have the information and time they need to submit competitive proposals.

- Those reviewing the RFP should place substantial weight on Race & Social Justice outcomes.

Several city departments have experience running a Request for Proposals process, including the Human Services Department, Office of Planning and Community Development, and Office of Economic Development.

Conversely, awarding funds in a sole-source manner (providing dollars directly to a single organization without an opportunity for others to compete) should be avoided because it typically lacks rigor and transparency — and might not produce the best results. [An exception to an RFP process may include short-term loans to nonprofit Public Development Authorities (PDAs) because (a) those loans will be paid back, (b) PDAs were created by the City government, and (c) PDAs have limited access to certain other funding sources such as the federal government’s COVID relief Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) program.]

The Recipient (track record):

- Is the recipient a nonprofit or for-profit?

- Is the recipient a reputable organization?

- Does the recipient have a strong track record of delivering results, such as tangible benefits to low-income or marginalized individuals?

- Does the organization make their financial statements available to the public?

- Have we examined the organization’s financial statements to verify financial need as well as future solvency?

- If the organization is seeking funds because it is under financial duress rather than to provide additive services to the public, what evidence is there that circumstances will improve and not require more funding to support the organization?

Their Proposal (either social service program or capital project):

- Is the money being used to help people in need or just the organization itself? (When donating money to charitable nonprofits, a best practice is often to make sure the organization is using less than 20% of its annual budget for its own overhead, administration, and fundraising. In other words, at least 80% is going “out the door” to help actual people in need outside of the organization.) This balance should be assessed at both the level of the organization as a whole and at the level of the proposed project seeking government funds.

- Is it a grant or a loan?

- If it’s a loan:

- What is the likely source of repayment? Cash flow? Fundraising?

- What are the secondary sources of repayment? Refinancing other loans to cash out some resources?

- What is the collateral of this public loan in case the loan is not re-paid as agreed?

- If it’s a loan:

- Are we permanently giving away public land (not ideal) or providing a long-term (e.g. 99-year) lease so that the public retains ownership of public lands while the organization still benefits and provides its services?

- More Criteria: See below for the different checklists for effectiveness: Social Service programs vs. Capital Projects…

Technical Assistance: If a promising organization seeking the funding could benefit from technical assistance to craft their application and/or produce the requested documentation, the city government should strive to provide it. For example, some organizations may have vital knowledge (language proficiency, cultural competence, trust in the community, etc.) but lack experience competing during an RFP process and/or tracking and reporting results. For example the Seattle Office of Civil Rights (SOCR) completed an RFP process in December 2020 and ensured smaller organizations received technical assistance with their applications.

2. ASSESSING EFFECTIVENESS:

The checklist for assessing a social service program is different than the checklist for a capital project. That’s because constructing a new low-income apartment building (capital project), for example, is very different than targeting income supports for low-income families. Both types of investments are worthy of consideration for your tax dollars to prevent homelessness and both should be appropriately assessed for their effectiveness — as city government should do for all social service programs and capital projects that are seeking your tax dollars.

A. Social Service Programs:

- NEED: What is the specific problem we are trying to solve? Is there data that demonstrates how big the problem really is so we know how much further we need to go? (“needs assessment”). Will solving this particular problem have a positive multiplier effect to improve other aspects of society?

- PROGRAM DESIGN: Is the program clearly designed to succeed?

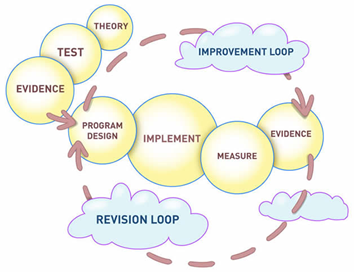

- Theory of Change: How does the program propose to make things better? What is the “theory of change”? Before providing money, we must ensure each program is designed with a clear and logical theory of change that explains how a particular intervention will directly result in the outcomes sought, rather than just hoping for results because the need is great or the program’s organizers have political connections to City Hall.

- Targeted Impact: Is the program targeted to those who need it the most and/or will the proposed dollar amounts proposed be sufficient to make a meaningful impact? Are we going upstream to prevent the problems from occurring rather than spending ineffectively on problems that already occurred.

- MEASURED OUTCOMES: Does the program define outcomes rather than just “inputs” and “outputs”? Rather than measuring only the “inputs” of dollars spent or the “outputs” of number of youth served, we must measure also the most relevant final outcomes (meaningful long-term goals) such as how many of those youth go on to get their high school diploma, obtain/keep a good-paying job, and/or stay out of the criminal justice system.

- BEST PRACTICE: Does the program already have a track record of achieving positive outcomes, as verified by others (rather than just self-reporting success)? Is there is evidence (yet) of it working here or in other similar cities? A “best practice” or “evidence-based” program has a greater chance of truly helping people. Potential sources for evidence-based programs proven to reduce crime and harm are highlighted by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy, the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy at George Mason University, and other independent, non-partisan research.

- PUBLIC / COMPETITIVE REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (RFPs): discussed above.

- PERFORMANCE-BASED CONTRACTS: Does the organization see the benefits of performance-based contracts? The contract can provide an agreed-upon framework for measuring results, feedback, and continuous improvement. If the organization does not achieve outcomes, the City could provide technical assistance or eventually move those funds to other organizations that can achieve the results for residents in need. As the funder, I believe the city government’s focus should ultimately be on achieving positive outcomes for Seattleites, rather than on sustaining the organizations with tax dollars.

- EVALUATIONS: Are there process evaluations and outcome evaluations set up at the beginning to track and report results and provide feedback? The more money we are investing in a particular, untested intervention, the more it might warrant a higher quality evaluation.

While presented in much more detail above, the approach above is consistent with my amendment on “effectiveness” approved by City Council to the JumpStart spending bill (CB 119811) and similar to the process in awarding funds for the Seattle’s Equitable Development Initiative.

B. Capital (Construction / Infrastructure) Projects (not owned by the City government):

Minimum Docs Needed to Assess a Proposal:

Based on my experience, I believe the following documents are needed for any funder (the city government with your tax dollars, in this case) to reasonably understand both the physical and financial parameters of the proposed project. Receiving consistent information from each proposed project also enables the funder to compare the relative benefits, challenges, and feasibility of each project. (The list below is similar to the basic information members of our State Legislature ask for when considering funding requests from community groups.)

- A detailed description of the proposed project, including the physical structure(s), community engagement, direct beneficiaries of the project, and intended outcomes.

- Proposed Sources and Uses of all funds. Where are all of the dollars coming from and how will they be spent? Sources should include the requested City funds and Uses should include the construction / renovation budget (if applicable), any real estate developer profit / fee and any loans (along with financial terms of any loans). Do they need our money and will it be spent wisely?

- Certified historical operating statements of the project (if the project already exists) with line item detail of revenues and expenses (including any City subsidies and/or tax exemptions as well as any debt service on any loans). How well has the project been operating?

- Projected (proforma) operating statement for at least the next five (5) years with line item detail of revenues and expenses (including any City subsidies and/or City tax exemptions as well was debt service on any loans). We should consider how well the project is likely to operate over the long-term.

- The most recently available independent audit of the project and/or organization to be receiving the city subsidy (if the project or organization already exists).

- Drawings, diagrams, photographs, and maps of the proposed project, including a site plan.

- A detailed list of direct public benefits resulting from the proposed project.

- Any other documents pertinent to determining financial need, feasibility, and public benefits.

Note: A City government office adept at assessing capital projects is our Office of Housing. Each year OH issues Notices of Funding Availability (NOFAs) that enable nonprofit housing organizations to apply for Seattle Housing Levy funding to help build or preserve affordable housing throughout Seattle.

By employing basic accountability checklists like those detailed above, your city government’s policymakers can ensure that your tax dollars are deployed in an effective manner to achieve the positive outcomes we all want for Seattle. Less rhetoric and more results for our city.

# # #

Posted: December 13th, 2020 under Councilmember Pedersen